⚠️ This review contains spoilers and refers to sensitive issues, including sexual assault and abuse.

After 21 volumes and 80 chapters, I've finally come to the provisional* end of a manga series whose characters have taken on the familiarity of old friends. Endearing, relatable and, at times, hopelessly infuriating. Saying goodbye to them was accompanied by a quiet sense of loss I'm sure the two Nanas would implicitly understand. So what was it about

Nana that made me stick with it for so long?

Nana follows two young women who move to Tokyo in search of their dreams at key junctures in their lives. A frivolous airhead who attaches herself to men too readily and a fiercely independent punk rocker set on making it as a lead vocalist, on the surface, Nana K. (a.k.a. Hachi) and Nana O. share little more than a name and the same train journey. Nevertheless, they make an improbable connection.

Both Nanas are seeking fulfilment, whether through romantic relationships or career success, and their attempts to establish their own versions of happiness and place in the world, however transient or wrongheaded, are in turns moving and frustrating. There's a constant sense of something unrealised, of bittersweet yearning that creates a sense of nostalgia; this reflects the displacement of that transitional twenty-something period all too well, when you're no longer a child but haven't quite figured all this adulting business out. I began reading it during that awkward limbo between finishing my degree and my own search for my first real job, and it really resonated with me. However, every reader is likely to find something in both Nanas to relate to.

As the series progresses, Yazawa draws a touching relationship between the two leads that presents a complex exploration of female friendship in its many shades

– sometimes protective and devoted, sometimes jealous and possessive, sometimes estranged and regretful. Similarly, there's an acknowledgement of the flaws in each character and relationship, giving the series an undercurrent of darkness that belies its trendy, shojo-appropriate (yet exquisitely drawn) trappings. This focus on twenty-something women and their platonic relationship is

unusual in manga. Because, despite their romantic entanglements (particularly those of Hachi,

cough), it's this enduring, intense relationship

– not the obsessive Sid

–Nancy love between Nana and Ren or the lopsided rock star

–fan-girl dichotomy between Hachi and Takumi

– that forms the true love story and heart of the manga.

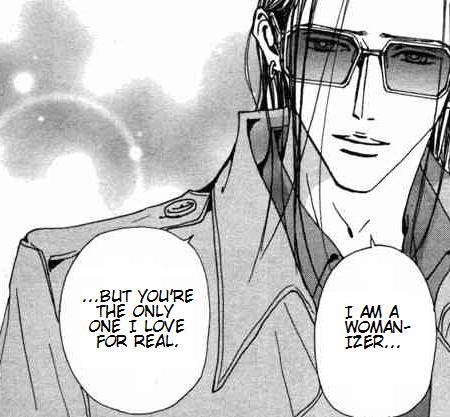

Unfortunately, this is something that I feel Yazawa loses sight of in the latter half of the series. While the eventual rift between Nana and Hachi is an important and inevitable stage of young adult growing pains, the series protracts this phase excessively. In doing so, it loses its most compelling draw. Characters are reduced to pining after each other and their romanticised past together, but don't act on their impulses, instead remaining static within unsatisfactory, oppressive situations. Nana longs to break free of an all-consuming relationship she has outgrown; Hachi, meanwhile, resigns herself to the life of a dutiful housewife and mother-to-be, the 'number-one second priority' to a selfish, emotionally (and, on a few occasions, physically) abusive, philandering, workaholic husband. Thank God he's pretty.

It's unclear whether we're supposed to root for Hachi and Takumi as a couple. Their relationship is never painted as ideal, but Takumi has enough moments of surprising tenderness and consideration that Hachi remains drawn in by him. This is, of course, textbook emotionally abusive behaviour, and Yazawa occasionally lampshades it

– the recurring metaphor of the dark fairytale (Cinderella losing her glass slipper; the princess in the tower falling in love with her captor) applies to Hachi as well as Reira.

However, for both these characters, Takumi's hot

–cold temperament seems a factor of his toxic allure, and, as the driving force behind Trapnest's success, the impression is given that his ruthlessness is the cost of his genius, which is presented as an otherwise admirable trait. Most disappointingly, Hachi's rape is glossed over and latter volumes and flash-forwards imply that, while Hachi and Takumi eventually drift apart, he has softened into a marginally more sympathetic character, suggesting that Hachi's patience in this relationship is a virtue, if not enough to save them.

Yazawa's exploration of the hidden complexity of each character is one of

Nana's main strengths; nothing is simple, everyone is fighting their own internal battles. Learning to be kinder, more understanding, is perhaps the most important takeaway of the series. However, the most interesting part of conflict is showing how the characters deal with it and grow as a result, but in

Nana, the main characters seem unaware

– or terrified

– of their agency, doing little to change their realities for several volumes. For the most part, their melancholic situations are only disrupted by erratic twists of fate that lie beyond them: a chance invitation to a birthday party; a tragic accident.

Accordingly, Nana and Hachi diminish as characters, with the focus broadening to the two main bands in the series, Blast and Trapnest, and a roster of new, only vaguely interesting filler characters apparently intended to compensate for the ever-widening gap between Nana and Hachi. At this point, the characters plunge into a seemingly unending downward spiral, and the darkness inherent in the series threatens to overwhelm, washing over everything with a heavy sense of futility. To reiterate: shiz gets

dark.

While there are small moments of levity and redemption (and this stasis is something Yazawa would undoubtedly have addressed in future volumes), the characters' inability

– or apparent unwillingness

– to save themselves from drowning gives the reader a feeling of ambivalence. While you want the two Nanas to reunite and accept the love they don't seem to think they deserve, it's difficult to continue to root for characters who don't even root for themselves.

Interestingly, I feel Yazawa paces her shorter, earlier work,

Paradise Kiss, better. Its protagonist, Yukari, engages in a similarly intense, unsustainable relationship with narcissistic artistic 'genius' George; however, it isn't unnecessarily drawn out, and Yukari shows real growth over the course of the series. Of course,

Nana leaves a more lasting impression, and the strength of its characters and their touching group dynamic (and the anticipation of a game-changing twist hinted at by the narration and flash-forwards) are just enough to sustain the series through its more sluggish moments. It could even be for this reason that Yazawa felt compelled to extend the story past its natural lifespan.

The 'final' two volumes of

Nana pick up its earlier momentum; the two Nanas' paths intersect again, and a devastating twist pushes everyone to reassess their relationships. The death of one of the core characters is treated with the gravity it calls for; this makes for a heartrending and heavy, yet important, volume, showing death in all of its anguish and numbness. It's likely this would've catalysed even more much-needed change, though all we have to go on are the clues dropped by the tantalising, if sometimes disorienting, flash-forwards.

In a way, that Nana is unfinished adds to its iconic status; for Yazawa's characters, nothing is clear-cut, so the lack of resolution is fitting, in a way (albeit unsatisfying). It also gives scope for interpretations as open-ended as the characters' destinies;

what happens between the final events shown and the glimpses into their future? In the future timeline, once again, the two Nanas are at a crossroads; Nana has fled to England, and Hachi is stuck, unable to envision her life without her.

I'd like to think that this would've finally opened the way for Hachi and Nana to heal and grow while apart from each other, though still connected, a bit like how Lena Dunham described the relationship progression in

Girls: 'Like, part of figuring out friendship is realising that you don’t have to either be roommates who spend every single moment knowing where the other is, or stop speaking entirely. There’s a more mature version of being connected.'

In the future scenes, Yazawa teases the beginnings of inner change. Throughout the series, Hachi has struggled with co-dependence issues, while Nana has battled with her pride; however, the former is now estranged from, if not broken up with, Takumi, while the latter, although still too proud to accept others' help, is singing anonymously in a small bar, renouncing the larger-than-life persona she has constructed.

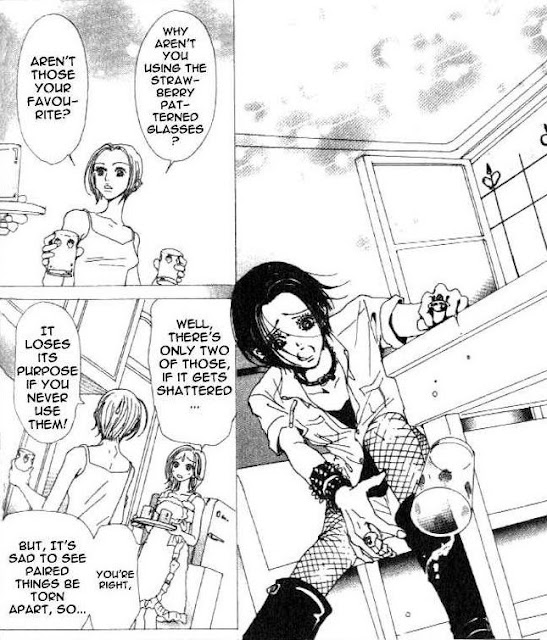

They may no longer share baths and the same bed or mirror each other in terms of life stage (as embodied by their parallel names and the palindromic apartment number, 707). But that's OK

– they'll always have that time and place together. And, with each still holding a key to room 707, every once in a while, there's a small chance they might even return, just as I hope Yazawa will one day.

*

At least, the point Yazawa sadly stopped working due to long-term illness. The series has been on indefinite hiatus ever since. It seems increasingly unlikely that it'll be picked up again at this stage, but a girl can hope.

If you liked this, please consider fuelling my next post by slinging a cup of coffee my way.

↓

Comments

Post a Comment

Did this post tickle your pickle? Let me know in the comments below.